NASA/CXC

Astronomers have discovered evidence for the farthest “cloaked” black hole found to date, using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. At only about 6% of the current age of the universe, this is the first indication of a black hole hidden by gas at such an early time in the history of the cosmos.

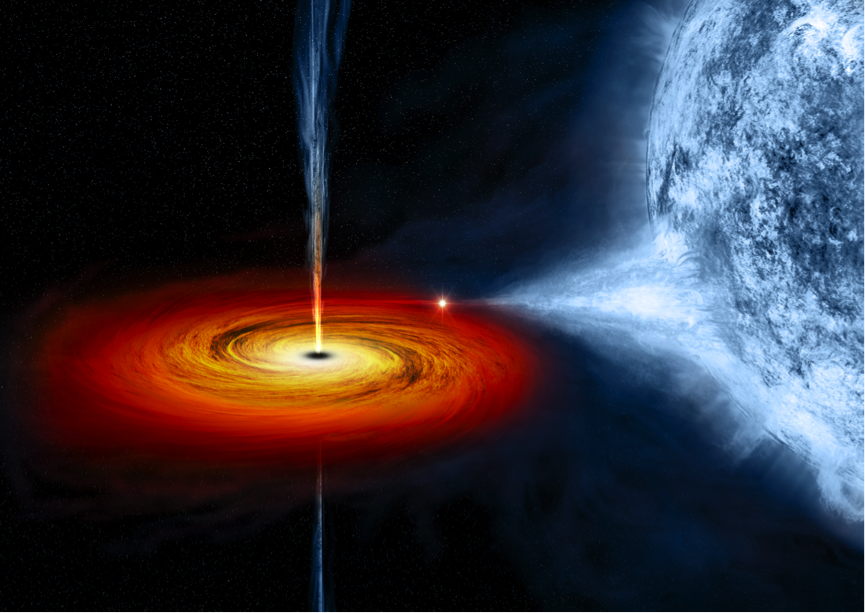

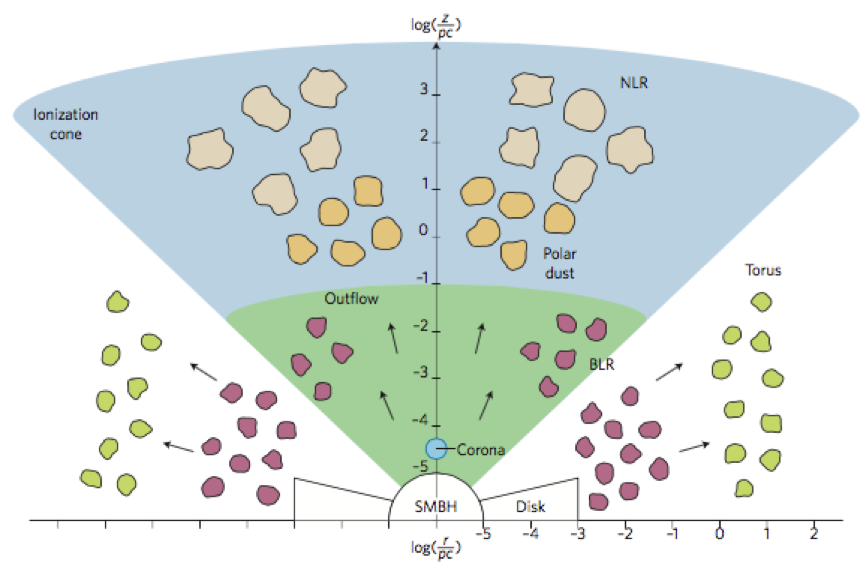

Supermassive black holes, which are millions to billions of times more massive than our Sun, typically grow by pulling in material from a disk of surrounding matter. Rapid growth generates large amounts of radiation in a very small region around the black hole. Scientists call this extremely bright, compact source a “quasar.”

According to current theories, a dense cloud of gas feeds material into the disk surrounding a supermassive black hole during its period of early growth, which “cloaks” or hides much of the quasar’s bright light from our view. As the black hole consumes material and becomes more massive, the gas in the cloud is depleted, until the black hole and its bright disk are uncovered.

“It’s extraordinarily challenging to find quasars in this cloaked phase because so much of their radiation is absorbed and cannot be detected by current instruments,” said Fabio Vito of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, in Santiago, Chile, who led the study. “Thanks to Chandra and the ability of X-rays to pierce through the obscuring cloud, we think we’ve finally succeeded.”

The new finding came from observations of a quasar called PSO167-13, which was first discovered by Pan-STARRS, an optical-light telescope in Hawaii. Optical observations from these and other surveys have detected about 180 quasars already shining brightly when the universe was less than a billion years old, or about 8 percent of its present age. These surveys were only considered effective at finding unobscured black holes, because the radiation they detect is suppressed by even thin clouds of gas and dust. Since PSO167-13 was part of those observations, this quasar was expected to be unobscured, too.

Vito’s team were able to test this idea by using Chandra to observe PSO167-13 and nine other quasars discovered with optical surveys. After 16 hours of observation, only three X-ray light particles were detected from PSO167-13, all with relatively high energies. Since low-energy X-rays are more easily absorbed than higher energy ones, the likely explanation is that the quasar is highly obscured by gas, allowing only high-energy X-rays to be detected.

“This was a complete surprise”, said co-author Niel Brandt of Penn State University in University Park, Pennsylvania. “It was like we were expecting a moth but saw a cocoon instead. None of the other nine quasars we observed were cloaked, which is what we anticipated.”

An interesting twist for PSO167-13 is that the galaxy hosting the quasar has a close companion galaxy, visible in data previously obtained with the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) of radio dishes in Chile and NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Because of their close separation and the faintness of the X-ray source, the team was unable to determine whether the newly-discovered X-ray emission is associated with the quasar PSO167-13 or with the companion galaxy.

If the X-rays come from the known quasar, then astronomers need to develop an explanation for why the quasar appeared highly obscured in X-rays but not in optical light. One possibility is that there has been a large and rapid increase in cloaking of the quasar during the three years between when the optical and the X-ray observations were made.

On the other hand, if instead the X-rays arise from the companion galaxy, then it represents the detection of a new quasar in close proximity to PSO167-13. This quasar pair would be the most distant yet detected.

In either of these two cases, the quasar detected by Chandra would be the most distant cloaked one yet seen, at 850 million years after the Big Bang. The previous record holder has been observed 1.3 billion years after the Big Bang.

The authors plan to follow up with more observations to learn more.

“With a longer Chandra observation we’ll be able to get a better estimate of how obscured this black hole is,” said co-author Franz Bauer, also from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, “and make a confident identification of the X-ray source with either the known quasar or the companion galaxy.”

The authors also plan to search for more examples of highly obscured black holes.

“We suspect that the majority of supermassive black holes in the early universe are cloaked: it’s then crucial to detect and study them to understand how they could grow to masses of a billion suns so quickly,” said co-author Roberto Gilli of INAF in Bologna, Italy.

A paper describing these results is accepted for publication in Astronomy and Astrophysics and is available online. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center controls science and flight operations from Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Other materials about the findings are available at:

http://chandra.si.edu